Chapter 21: The Muse of Sculpture

|

| academicnudes19thcentury.blogspot.com |

|

| click to enlarge |

Only the tiniest of sprites —

like Tinker Bell — should merit them!

|

| source |

Because the children depicted with the Muse of Painting were not winged, I decided to drop the wings on this little attendant as well.

I looked at several renditions of blond hair by Michelangelo and noticed that he would sometimes add a tint of red or orange to the yellow. Perhaps the Muse of Sculpture is a strawberry blond.

The finished Muse of Sculpture is below.

|

| click to enlarge |

|

| click to enlarge |

Chapter 22: The Muse of Architecture

In contrast to the Muse of Sculpture, my greatest departure from the Bürkner etchings is with the Muse of Architecture.

I omitted the small angel, in part because I thought it cluttered the

composition, and in part because I reckon that a muse really doesn't

need anyone to whisper direction into its ear. I also simplified the

architectural model from six columns to four columns. |

| click to enlarge |

My biggest change was in the figure of the muse itself. I think the Muse of Architecture should be more elegantly dressed than Bürkner's version, and have a softer face. My friend Yvonne, whose Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin inspired this mural, made an astute observation. She looked at the muse's face and asked, "Is this one of your friends, because the face is a more modern depiction of beauty?"

|

| www.filmreference.com |

The muse's attendant bears watching.

I fear that he is a bit of an imp.

The finished Muse of Architecture is below.

The finished Muse of Architecture is below.

|

| click to enlarge |

|

| click to enlarge |

Chapter 23: The 4 Styles

Pompeian murals fall into one of four styles of decoration, and I thought this would be a good point in the Pompeii Room project to stop and talk about them. I'll do an abbreviated description of the four styles, and then you can determine for yourself how my own mural would be characterized (bearing in mind that it's still a work in progress).

Pompeian murals fall into one of four styles of decoration, and I thought this would be a good point in the Pompeii Room project to stop and talk about them. I'll do an abbreviated description of the four styles, and then you can determine for yourself how my own mural would be characterized (bearing in mind that it's still a work in progress).

|

| studyblue.com |

Below is another example of the First Style (also called Masonry Style).

|

| www.accla.org |

|

| Grand Illusions | Phaidon | Cass | Leighton | 1988 |

The Second Style (also called Architectural or Illusionist Style) was an artisitic revolution. The Pompeian rooms, which usually did not receive a lot of light, were now painted to bring the outdoors inside, and to give the illusion of opened space. The home of P. Fannius Synistor (which is the inspiration for my own room) included a bedroom (cubiculum) with an imaginary cityscape, below.

|

| click to enlarge | Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, spring, 2010 |

|

| click to enlarge | Pompeii: The Last Day | Wilkinson | 2003 |

An important element throughout the Second Style was trompe l'oeil details. Bowls of fruit, vases of flowers and musical instruments abounded. Below, the scroll, ink pot, wax tablets and piles of coins were a not-too-subtle reminder of the homeowner's education and wealth.

|

| click to enlarge | The Art of Pompeii | Magagnini | de Luca |

Another facet of the Second Style was the depiction of monumental

figures, and there's no better or more famous example than the Salon of

Mysteries, in the Villa of the Mysteries, below.

|

| sites.davidson.edu |

The Third Style (also called Ornate Style) was a reaction to the open vistas of the Second Style. The Pompeians were ready to reclaim and flatten most of the wall space that they had once opened up.

|

| Pompeii | Coarelli | Riverside | 2002 |

|

| click to enlarge | www.boundless.com | monm.edu |

The Fourth Style is the culmination of all the previous styles, and probably because so much of Pompeii was rebuilt after an earthquake in 62 A.D., it's the style most often found in Pompeii.

|

| Pompeii | Coarelli | Riverside | 2002 |

Chapter 24: Chairs for the Pompeii Room

The challenge of finding the right furniture for the Pompeii Room has been to find a set of chairs that are neoclassic — either klismos chairs or a style that was inspired by klismos chairs.

As I mentioned in an earlier posting, here, my friend Sandy and I have been visiting a monthly brocante in our town of St. Petersburg, Florida. When we saw these chairs several months ago, Sandy agreed with me that they would be perfect for the Pompeii Room, so much so that she insisted on gifting me with them!!

The chairs came with this mustard yellow paint rubbed on them, which I suppose was meant to make them attractive in a "shabby chic" sort of way. The gaudy color probably worked in my favor because I guess that a lot of people could not see past it to recognize the chairs' wonderful details.

Each chair has a rope twist decoration and a handsome brass medallion, and therein lies a story:

|

| www.neptunepictues.com |

The victory, plus Nelson's heroic death, inspired a British craze of all things naval, and that in turn impacted the neoclassic style that was sweeping both Britain and the Continent at the time.

|

| 1stdibs.com |

|

| click to enlarge | 1stdibs.com | wakefieldscearce.com | 1stdibs.com |

Here are three Regency chairs of similar design, each with the rope twist decoration and buttons that are also featured on my chairs. You can click on the image to see the details.

I'm getting my Regency chairs refinished, and I'll be showing them off at a later date, as all the elements of the room come together.

And now, back to the mural . . .

This week I'm adding coral branches to the mural!

Coral, once believed to be a sea plant, is actually the cumulative skeletal remains of living animals called polyps. For thousands of years, many cultures have viewed coral as a decorative gem as well as protection against disease.

In Ancient Rome, coral was believed to protect against childhood disease and to avert evil, and it's still seen as good luck in Mediterranean countries and places like India, Tibet and Japan.

|

| Piero della Francesca | Rizzoli |

|

| Mantegna: I Maestro del Colore | Fratelli Fabbri |

|

| Mantegna: I Maestro del Colore | Fratelli Fabbri |

I'll be using della Francesca's and Mantegna's coral as models, but . . .

|

| PubHist.com |

. . . I wanted to include later images of coral to illustrate how the

gem was revered through the ages. The painting above, by Jan Claesz,

dates to circa 1609, and shows a girl who has both a coral necklace and a

rattle that incorporates pink or white coral at its tip.

|

| Christie's auction |

Such rattles often doubled as whistles. Above are English rattles dating

to the early 20th century, a full 400 years after the rattle in Jan

Claesz's painting. My blogging friend Rosemary, of Where Five Valleys Meet, says of these rattles, "The coral section of the English Victorian rattles was there to sooth

the baby's gums when teething. Coral did not chip or splinter, and is

cool to the touch. The coral also provided some comfort and reassurance

to parents because of its mystical protection, as you have mentioned."

Incidentally, these four rattles recently sold at auction for approximately $2200, total, which I imagine would make a collector of such items very happy.

I'll be hanging the coral branches

over the mural's three smaller garlands.

|

| click to enlarge |

Above are the finished corals. As you can see, I scoured the seas for three branches that were similar in shape as well as size.

Chapter 26: The Ideal City

This week, I'm painting a cityscape in that blue portion of the mural that suggests a window, but which so far has looked very blank and flat. My intention is to create fantasy architecture as the Pompeians would, and also to add some depth to the mural.

During the Third Style of Pompeian mural painting, which I described here,

a unique depiction of architecture evolved. At a glance one sees

buildings, but upon closer inspection, the structures are usually simply

multi-layered facades with elongated, spindly columns, much like stage

settings. The Pompeians were avid theater-goers, and it is as though

they desired theatrical backdrops in their homes, for the drama of their

own lives.Chapter 26: The Ideal City

This week, I'm painting a cityscape in that blue portion of the mural that suggests a window, but which so far has looked very blank and flat. My intention is to create fantasy architecture as the Pompeians would, and also to add some depth to the mural.

|

| L'Ornement Polychrome, Series I & II | Auguste Racinet, 1873 |

Before I started painting my urban area, I deliberated over what colors to use. I initially considered using blues and grays, which would have given the impression of distance. In the end, though, I decided to use golds and greens to complement the Muse of Architecture, the garlands, and the trophy walls.

|

| michiganexposures.blogspot.com |

|

| click to enlarge | Karl Friedrich Schinkel: A Universal Man |

|

| click to enlarge |

The pediment of my mural temple

is the same proportion and design as

the pediment of my house, seen below.

|

| click to enlarge |

Above is the finished city.

Note that the temple is open to the front and back,

and that the temple door is

a portal, within a portal, within a portal, within a portal.

|

| click to enlatge |

I decided that the Pompeian Room should include an olive branch for my own good luck, and that I would hang it from a substantial blue satin ribbon.

I bought blue satin for reference and enlisted my friend Sandy to sew the cloth as it appears above. (I've looked at any number of murals with delicate ribbons and decided I wanted something with a little more gravitas.)

|

| click to enlarge |

The center panel "window" is now complete, and I'm satisfied that there is some sense of depth.

Next week I'll add some elements to the foreground, and that should help accentuate that sense of depth. What would you put in the foreground?

Chapter 28: The Golden Tripod

In my last two postings, I created a sense of depth in the mural's window panel by painting a cityscape in the background and then hanging an olive branch in the foreground. I could have heightened the illusion of foreground by having the olive branch partially obscure the cityscape, but I didn't want to go that route.

So this week, I'm going to accentuate the mural foreground by painting an authentic Pompeian tripod in the area below the cityscape.

|

| photo-illustration, Mark D. Ruffner |

|

| Shapero Rare Books | villageantiques.ch |

|

| click to enlarge | sources below |

Pompeii, Coarelli, Riverside | The Treasury of Ornament, Dolmetsch, Portland House

Tripods in Pompeii were no less finely designed, and above is one of the more famous ones. It comes from the estate of a wealthy Pompeian woman named Julia Felix, daughter of Spurius. On the left is a photograph and on the right is a Victorian era representation of the same tripod. As you can see, the Victorians were wont to exclude certain details.

|

| Period Paper | amazon.com |

|

| click to enlarge |

|

| click to enlarge |

- I want to fill more of the alaea* panel without otherwise crowding it,

- I do want to give the impression that a rite is happening before the temple, and

- I want whatever I place in the basket to stand out against a lighter background.

|

| click to enlarge |

Next week I'll be filling the tripod's basket.

I hope you'll join me then!

Chapter 29: The Sacred Offering

|

| PhotoShop illustration, Mark D. Ruffner |

I decided to place peonies in the tripod basket that I revealed last

week. In the symbolism of flowers, the peony has many meanings, and one

is success. I'm using a symbol that can encompass many aspects of good

luck!

I'm taking some liberties here because the Pompeians probably never knew the peony; it was actually introduced to Europe from Asia at a much later date. (The artwork that I've used as a header comes from a 1663 engraving by Wencelas Hollar.)

Using real peonies for reference posed a problem for me because peonies

don't grow in the Florida climate. Nonetheless, I had a dozen peony buds

shipped to me at quite an expense. Because the buds were opening at

different rates, I was concerned that I wouldn't get an optimum

arrangement, and that the investment might become a waste.I'm taking some liberties here because the Pompeians probably never knew the peony; it was actually introduced to Europe from Asia at a much later date. (The artwork that I've used as a header comes from a 1663 engraving by Wencelas Hollar.)

So I hit upon the idea of setting up a table with a white background, and setting up a photographer's light on a tripod. The jug that you see above, the light, and the camera setting would not be changed a fraction until the end of the project.

Then I took each individual flower and set it in the jug, photographing it from multiple angles. The next day, as each flower opened a little more, I'd start the process all over again. Above you see two flowers that have been photographed in that manner. By the end of the week, I had a digital library of hundreds of flowers — all with the same light source — that could be digitally put together in endless flower arrangements.

Here you see the mural arrangement I came up with as it appears in PhotoShop. It has 18 layers, including the white background. Each flower is on a seperate layer so that it can be adjusted just as it would if one were arranging actual flowers.

|

| click to enlarge |

|

| click to enlarge |

|

| click to enlarge |

I will be adding elements between the muses and the garlands, but in order to do that in a logical way, I'll need to first direct your attention to another wall. I hope you'll join me in the next posting as I shift gears and work on what I call the transom!

Chapter 30: The Transom Solutions

When I moved into my house more than 25 years ago, it had changed very little since the 1940s. Upon entering, a guest would face two very disparate arches — a perfectly round one leading into the hallway, and an ovoid one that lead into what is now the Pompeii Room.

The two odd arches met at one point and created a design tension that bothered me to no end.

When I built bookcases on two living room walls, I neatly hid both arches by building a shelf that also connected the bookcases. For a number of years, the shelf was a display area for many collections that ringed the living room, much like a museum.

I simply needed to make sense of the transom by painting it as an architectural element that would unite both sides of the room. And so my goal is to transform the structure from a quirky transom into something akin to the top of a Roman triumphal arch!

Next week I'll reveal the first of three painted bas reliefs, and I'll start with that long central panel.

I hope you'll join me then — it's going to be fun!

In my last posting, I mentioned that I was going to paint my dining room's transom to look like the top of a triumphal arch. The little drawing above illustrates the effect I want to achieve in terms of a wider central panel and two smaller panels.

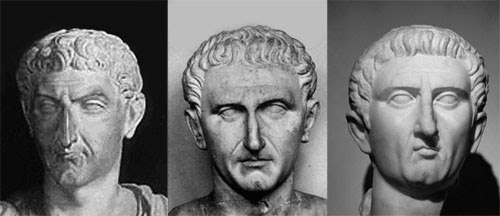

Here are three Roman triumphal arches, and in each of them you can see that the top's center plaque is equal to the width of the actual arch, plus its adjacent columns (It's interesting that there seems to have been a design rule, but then it's an obvious way to aesthetically divide the space.).

The arches, from top to bottom and in the order they were erected, are the Arch of Titus, Rome, circa 82 A.D.; the Arch of Trajan, Benevento, circa 117 A.D.; and the Arch of Constantine, Rome, 315 A.D.

sources, from top to bottom: tours-venice-italy.com | ancientrome.ru | studyblue.com

|

| click to enlarge |

I start out by outlining the design, then paint light medium tones. I then work into the darker tones, and finally add any highlights.

|

| click to enlarge |

In my next posting, I'll be filling the left niche, and what I put there will quite possibly be the major theme of the Pompeii Room. I hope you'll join me then!

Chapter 32: Five Good Emperors

(History buffs and authorities will have to excuse me, since all five reigned after Pompeii was already covered by ash. This will just have to come under the heading of artistic license!)

In fact the Emperor Titus, son of Vespasian, ruled when Pompeii was destroyed. Titus was succeeded by his brother, Emperor Domitian, whose reign was one of terror, at least for everyone in close proximity to him.

|

| art-prints-on-demand.com |

Nerva (30-98 A.D.) was the first of the Five Good Emperors, and a bas relief bust of him will fit into the niche on the left side of my transom.

|

| nndb.com | sacredantinous.com | en.wikipedia.org |

One thing that has occurred to me is that the center bust appears to use the image of Caesar Augustus as a template. I will use that image, but narrow the head slightly and combine it with the smaller mouths seen in the other two busts.

Here's my version of Nerva. Because of his age (65 was quite advanced by Roman standards) and because he appears to have had a smaller jaw, you will notice that I have given Nerva slightly hollowed cheeks. Next week we'll look at the second of the Five Good Emperors, Trajan.

Chapter 33: Painting Emperor Trajan

In my last posting I dedicated a dining room bust to the Emperor Nerva. His predecessors had been so cruel and tyrannical, and Nerva was so just by comparison, that he was perceived by the army to be weak. Fearing his own assassination, Nerva adopted the popular Trajan, a general of Spanish origin, and named him his successor. Nerva thereby placated the restless army, and soon thereafter died peacefully in his sleep.

|

| click to enlarge | map by Mark D. Ruffner |

|

| en.wikipedia.org | trauwerk.stanford.com | artflakes.com |

Here's my version of the Emperor Trajan. And below is a perspective of the finished transom.

|

| click to enlarge |

Chapter 34: Painting Emperor Hadrian

In my last posting, I dedicated a bust on my dining room's transom to Emperor Trajan. Trajan died without an heir, but is reputed to have named his cousin, Hadrian (76 A.D.-138 A.D.), on his deathbed.

Hadrian is always depicted with large and tightly permed curls around his forehead, and he was the first of the Roman emperors to sport a beard. He spent much time raising the standard and readiness of the army, and had a preference for wearing military uniforms.

|

| Hadrian and Antinous | www.britishmuseum.org |

|

| The Pantheon | commons.wikipedia.org | trekearth.com |

|

| Hadrian's Wall | photograph by Oliver Benn/Getty Images |

Hadrian was considered wise and just; he revised the legal code, and though he did not abolish slavery, he diminished it and its excesses.

My design for the portraits of the remaining three emperors somewhat resembles a plaque by Josiah Wedgwood, or perhaps a roundel by Andrea della Robbia.

I chose a golden frame to complement the golden garland that hangs above. I think it's quite appropriate that this image of Hadrian is positioned above the Muse of Architecture. (I'll show the whole wall a little later.)

I hope you'll join me next week when I reveal a portrait

of the fourth of the Five Good Emperors.

Chapter 35: Painting Emperor Antoninus

|

| Antoninus Pius | icollector.com |

|

| photo illustration, Mark D. Ruffner |

Though he is remembered as one of the Five Good Emperors, Hadrian had sunk into a state of paranoia in his last days, and had condemned a number of senators to death. Antoninus saved the senators who remained and then went on to adhere very closely to Hadrian's programs. He also convinced the Senate to deify Hadrian, and though now emperor, when he went to the Senate, Antoninus took care to physically support his aged father-in-law. The Romans took note of all these acts and qualities and gave the emperor the name, "Antoninus Pius," by which history has always remembered him.

Antoninus Pius' major legacy was his revision of the Roman legal code, and in particular he instituted the rule that a defendant should be presumed innocent until proven guilty. He also believed that special circumstances could be more important than the letter of the law. Antoninus Pius extended friendship to Jews and Christians, and coincidentally had the calmest reign (138-161 A.D.) in Roman imperial history.

Some historians say that in that regard, he benefited from following in the footsteps of Hadrian. His governing style was one of delegation, and in fact Antoninus Pius never left Italy during his reign.

My dining room portrait of Antoninus Pius follows the same style as Hadrian's ...

... and he is placed above the Muse of Sculpture (I'll be showing the nearly completed wall later in the month.).

Chapter 36: The Last of the Five Good Emperors

|

| Marcus Aurelius | photo illustration, Mark D. Ruffner |

|

| the young Marcus Aurelius | mutualart.com |

After Antoninus Pius adopted him, Marcus Aurelius married the emperor's daughter, Faustina the Younger, who was — through his adoption — also his step-sister. Thereafter he was given high appointments at a very early age, though his quick ascent did nothing to change his good, studious character.

|

| a bust of Lucius Verus from the Metropolitan | commonswikimedia.org |

Thereafter, Marcus Aurelius ruled alone until his death in 180 A.D. He is probably best remembered for his personal musings, Meditations, and for being the quintessential philosopher-king. Ironically, this scholarly emperor spent much of his reign away from Rome, fighting German tribes along the empire's borders.

Here's my portrait of Marcus Aurelius, in the style of Hadrian's and Antoninus Pius'. It hangs above the Muse of Painting, on the opposite wall.

I hope you'll join me next week when I add labels to these portraits, making use of a design by none other than Michelangelo.

Chapter 37: Painting the Legends

I thought it appropriate to label the roundel portraits (the last three of the Five Good Emperors), and so I cast about for a good label design to do them justice.

|

| source |

This type of design is called "strapwork," because the shapes mimic the artful designs that leather and metal straps of Michelangelo's time featured. My blogging friend Theresa of Art's The Answer has posted extensively about strapwork, and you can read more about it at her site, here.

Below is the primary wall of the Pompeii Room, finished above the green bar. I'll be doing more work on the green and red areas a little later.

|

| click to enlarge |

Chapter 38: Gifts from Vesuvius

|

| www.lovethesepics.com |

Joan is a very generous fellow, because he parted with four little gems that he had picked up in the rubble of Pompeii.

When they got home, Peter and Allan gave me these artifacts in the handsome presentation you see above. You can imagine how surprised and delighted I was, especially since I have never been to Pompeii!

The first item is a piece of pumice measuring approximately one inch. When Vesuvius erupted, there were two phases of the destruction, which lasted over two days. First, on the morning of August 24, 79 A.D., there was a tall column of material that shot up from Vesuvius and then fell like rain. This is named the Plinian phase, so-called after Pliny the Younger, who witnessed the eruption at a distance and who left the only eye-witness account.

Light and small pumice like the one above rained for 18 hours, and while the pumice rain was not a direct threat to human life, it accumulated to probably more than eight feet, causing roofs to collapse and buildings to fill with the equivalent of heavy Styrofoam pellets.

By the morning of August 25, the residents still in Pompeii realized that the city was uninhabitable. There was a mass exodus, but for those who had remained, it was already too late. The second, or Peléan phase of eruption started. (Peléan is a reference to the observations of the 1902 eruption of Martinique's Mount Pelé.)

In that phase the 18-hour column collapsed and a glowing cloud of high-temperature gas and dust raced down Vesuvius at approximately 60 mph (100 km), killing anyone who remained in its path.

The second item is a piece of lava, shown above. Ironically, the rain of pumice and dust which initially destroyed Pompeii, also preserved the city against the lava that followed. This piece measures 1¼".

Finally, the third and fourth items are two mosaic pieces, each less than ½". Some mosaics were scattered to the winds, as the weight of the pumice destroyed ceilings, walls and floors.

I will be proud to permanently display these interesting and historic artifacts in the Pompeii Room when it is completed!

Chapter 39: A Dove for Marcus Aurelius

Two postings ago, I revealed the primary wall of the Pompeii Room, finished above the green and red that could be considered a wainscoting.

Today, we'll look at the opposite wall, where I'll add a mourning dove on the ledge above Marcus Aurelius' portrait; it will complete that portion of the mural to the same degree.

|

| Mosaic from fineartamerica.com, all others, The Art of Pompeii | Magagnini | de Luca |

|

| birdinginformation.com |

|

| Click to enlarge |

Here's the Marcus Aurelius corner, complete above the green bar. We'll be working on that green and red later. But first, there's work to be done on that yellow section, to the right of the columns.

I hope you'll join me as the mural encompasses the kitchen door and inches towards the living room!

Chapter 40: The Kitchen Door Frame

In my posting No. 39, I revealed the corner of my dining room dedicated to Marcus Aurelius, below:

Now it's time to move to the the yellow wall and tackle the kitchen door and the area that surrounds it, as seen in the diagram above and the image below:

Oh, oh, the color photo didn't turn out too well, so we'll make it a duotone and pretend it's an old archival image. The door frame was put up before I had any thought of a mural, so it's not Pompeian in style. I'd describe it as Elizabethan.

The door frame was designed around two angelic furniture details that were a Christmas gift many years ago from my sister-in-law, Alice. The rest of the door frame was built to my design by a very talented artist, Jerry Jones. When I designed the door, I was actually thinking of that great English treasure, Knole House, below.

|

| knoleconservationteam.wordpress.com |

I've painted the door frame to look like stone, and the rest of the wall will match the other masonry in the room.

Here's the finished kitchen door and the base coat for the wall, with masonry lines penciled in.

If you look closely, you can see that I've penciled a pediment over the door frame. I hope the result will give it a slightly more Neoclassic feel.

And I hope you join me for the next posting,

when I paint the blocks, and mortar them into place!

No comments:

Post a Comment